from: Local history yearbook of the district of Ahrweiler 1988

from: Zeitschrift für Heilpädagogik 39th year, issue 8 August 1988, p. 525 - 540

Levana - both a reminder and a warning

Bad Neuenahr-Ahrweiler special school given the name "Levana School"

Gerd Jung

On the recommendation of the teachers and parents, by resolution of the district council on June 13, 1986 and with the approval of the school authorities on July 1, 1986, the school for the mentally handicapped (special school) in Bad Neuenahr-Ahrweiler has been called the "Levana School" since August 1, 1986.

In addition to the pure designation of the type of special school, i.e. in this case the school for the mentally handicapped as a form of special school, the name "Levana" is now added, which stands for a certain educational attitude, indeed more for a certain image of humanity.

"Levana"

The name "Levana" is associated with three historical events that were significant in the choice of the school's name:

First of all, "Levana" is the name of the Roman patron goddess of children; the meaning of the Latin word "levare" is: to raise, lift up, receive, accept.

Furthermore, "Levana oder Erziehlehre" is the title of the first widely used pedagogical work of the time, written by Jean Paul Friedrich Richter in 1806, a work that was probably the first to advocate the idea of "curative education". Jean Paul already recognized the educational importance of early childhood: " . . . but by educating we sow on a pure soft soil either cups of poison or honey; and as the gods to the first men, so we (physically and mentally giants to the children) descend to the little ones and bring them up or - down" (1806, 533).

And elsewhere: "The parental hand can cover and shade the sprouting seed, but not the blossoming tree. All the first mistakes are therefore the biggest;

and mental diseases, unlike smallpox, become more dangerous the younger you get them. Every new educator has less influence than the previous one, until finally, if one takes the whole of life for an educational institution, a circumnavigator does not receive as much education from all peoples taken together as from his nurse" (1806, 531).

Jean Paul understands the term "Levana" in the image of the plant world as the nurturing and growth of a small child into a large adult. The original figurative meanings of "kindergarten" and "adult" become clear here. In the kindergarten, children can grow up like little tender plants, as it were, while the adult presents himself as a personality that has matured through education and upbringing.

As an example of the many practical educational tips in his 350-page educational theory, here is a brief outline of Jean Paul's statements, which he makes under the heading "Areas, prohibitions".

In contrast to Rousseau, Jean Paul fundamentally considers the commandment and prohibition to be educationally necessary. There are some interesting practical tips here that are still relevant today, 150 years on, after many school reforms and educational theories:

"Do not take pleasure in commanding and forbidding, but in children's free action. Too frequent commanding is more to the parental advantage than to the child's" (1806, 619). "Forbid less often by deed than by word; do not snatch the knife away from the child, but let it put it away itself by word; in the first case it follows the pressure of another's power, in the second the course of its own" (620).

"Forbid in a low voice, that a whole ladder of amplification may stand free, - and only once" (623),

The fact that education, especially "curative education" or "counter-education", as Jean Paul calls it (1806, 531), means more than just commanding and forbidding, becomes clear when he says: "but even the camel does not trot faster in front of the whip, but only behind the flute" (625).

The third historical event with significance for the choice of the school name is the "Levana-Heilpflege- und Erziehanstalt für geistes- und körperschwache Kinder" (Levana Nursing and Educational Institution for Mentally and Physically Weak Children) founded in Baden near Vienna in 1856. It was one of the first educational institutions of its kind. Its founders and directors were the writer Jeanne Marie von Gayette, an admirer of Jean Paul, and the educationalists Jan Daniel Georgens and Heinrich Deinhardt.

The beginnings and the development of the Levana-Heil- und Erziehanstalt were not easy, in the following I refer to a dissertation by SELBMANN on Jan Daniel Georgens (SELBMANN 1982),

Georgens, the actual director of the institution, first moved to Baden near Vienna and rented the "Braunsche Villa" there. As there were initially no disabled children, Georgens and his staff began to educate the villa's gardeners' children and organize activities, games and gymnastic exercises for the children of the bathing guests. The initial popularity immediately waned when it became known that the institute was also to be a sanatorium for the mentally handicapped.

The first "Heilpflegling", an eleven-year-old girl from a noble family, entered the institution in June 1856. At the end of 1856, Georgens announced the official start of the institution's work for the spring of 1857. The advertising in the newspapers etc. was so successful that a change of premises became necessary.

In March 1857, Georgens and the members of the institute moved to the castle rented in Liesing near Vienna. Despite probably high rental costs - the institute not only had the building at its disposal, but was also able to use a park with a bathing establishment and swimming school, a large school garden and a rowing pond for education, teaching and therapy - the "Levana" was not actually a commercial healing and educational institute, but as a private institution without any state or other support, was dependent on credit from private sources. Despite all the financial constraints, the "Levana" not only took in children of wealthy parents, but also offered a refuge to sons and daughters of destitute parents.

Not least as a result of the death of two great patrons of the Levana Institute, its decline began in the fall of 1859, around three years after it was founded. Liesing Castle had to be abandoned and it was initially not possible to continue the Institute's work for financial reasons.

In 1860, Georgens again received financial support and rented a villa, this time on the Kahlenberg near Vienna. After efforts to obtain state support by taking on so-called "state foster children" failed, the number of pupils continued to decline and Georgens' most important employee Heinrich Deinhardt parted ways with him in the spring of 1861, the "Levana" institution finally came to an end in 1865.

The main reason for the closure of the institution was probably that "Levana" could not exist as a private institution without permanent financial support from the private sector, but the awareness of the need for curative education institutions and their support had not yet been reached at that time. In addition, the few funds received meant that no reserves could be built up. Further difficulties were caused by the simultaneous nature of too many projects and staff turnover.

Georgens and Deinhardt reported on their experiences in the educational work with mentally handicapped children at the Levana institution in lectures, which were published in the two-volume work "Die Heilpädagogik mit besonderer Berücksichtigung der Idiotie und der Idiotenanstalten" in 1861/1863 and in the "Medizinisch-pädagogischen Jahrbuch der Levana für das Jahr 1858".

It should be noted here that at this time terms such as "idiocy and idiots" were medical terms used to describe mentally handicapped people. How difficult it was to come to terms with the new terminology at this time is also shown by the job title of the relevant teachers, who were generally referred to as "Schwachsinnigenbildner" (SELBMANN 1982, 42).

The educational concept

In the following, the educational concept on which the Levana Institute was based will be briefly described, and comparisons with today's principles of teaching mentally handicapped pupils will be made. Basically, and this is almost revolutionary for the time, the educational ability of every mentally handicapped person is unquestionably acknowledged. For the first time, educational activities were given priority over medical applications.

The educational goals take into account both the personality of the disabled person with his or her joy of learning and willingness to learn, on the one hand, and the demands of society, such as the greatest possible independence and taking on employable work, on the other.

To this day, school efforts for the mentally disabled move between these two poles and attempt to take into account and combine both individual needs-oriented goals and social needs-oriented content.

The modern guiding principle of the guidelines currently in force for our form of special school reflects this ambivalence in the formulation: self-realization in social integration.

Back to Levana-Anstalt: In order to be able to support the children in a targeted and systematic way, a special educational and curative plan was drawn up for each individual child. Georgens and his co-authors developed methodical and didactic guidelines that are still valid today for teaching at the school for the mentally handicapped.

The importance of so-called occasional teaching is recognized and the demand is made that the disabled child "always and everywhere requires concrete, objective presentation" (according to SELBMANN 1983, 299). Further principles of teaching in a school for the mentally handicapped, which are still valid today, were pointed out more than 120 years ago:

"The teaching of the idiots must emphasize and dwell on that which is first in their interest and most accessible to their understanding . . . As with the activities and work exercises, the ability to abstract must of course not be used too early in the lessons, and the principle of vividness of the lessons allows illustrative means for the idiots which are inadmissible for healthy children" (after SELBMANN 1982, 94).

Play, gymnastics, activities and work and hiking, i.e. frequent school trips, are mentioned as so-called practical means of education. Much emphasis is placed on music and singing, and formal and gardening activities are described in detail.

Modern concepts of education for the mentally handicapped, such as "descriptive-comprehensive" or "action-oriented learning"; catchwords such as "learning on the spot", "learning to live" and "city as curriculum", i.e., for example, the project-oriented visit to the post office, the hospital or the supermarket and coping with these life situations as independently as possible, all these current ideas can easily be consistently developed further from the curative education concept of Georgens, Deinhardt and Gayette.

Integration, the big issue of today, was already a familiar concept for the authors 100 years ago.

While on the one hand they recognize the possibilities and necessities of special support for mentally disabled people, on the other hand they note that the success of education depends essentially on whether a regulated coexistence of disabled and non-disabled children can be guaranteed. They hope that the example of non-disabled children will lead to greater learning success: "during the walks (meaning prepared classroom walks), the attention to occurring phenomena such as the desire for movement in the idiots needs to be stimulated and determined, for which the example of the healthy is far more effective than the requests of the accompanying educator" (according to SELBMANN 1982, 113).

The founders of the Levana Institute see the term "Levana", understood as the acceptance of the disabled person, as being realized in the recognition of the fundamental educational ability of mentally disabled people and in the constant effort to integrate them into society despite the need for special educational means and to give them as much equipment as possible "so that the individuals concerned do not become a 'burden' on their families and society or become 'useful' people . . ." (after SELBMANN 1983, 292).

The Levana principle

The significance of the name "Levana" for the Roman patron goddess of children becomes clear when you consider the solemn act of "levare", the rite of taking in by the then overbearing father of the family, the Pater Familias. Two thousand years ago, he could decide over the life and death of his newborn children simply by picking up the infant lying in front of him or by refusing to do so. The raising and acceptance of the child in the literal sense was carried out and pronounced. The New Testament has handed down a very old expression of this legal language: "This is my beloved son, in whom I am well pleased!" However, if the father remained silent and ordered the abandonment, then the wet nurse and mother had prayed in vain (according to Möckel 1984). Children with deformities or disabilities probably had little chance of survival here.

The term >Levana< therefore stands for the fundamental unconditional acceptance of fellow human beings, regardless of their characteristics and capabilities.

The Levana principle thus makes it clear that not only is there no such thing as a "life unworthy of life", but also that there is or must be no such thing as a human being who is more or less worthy of life.

At this point, we often struggle with our inner convictions. Such phrases about the equal value of being human quickly become mere lip service, especially in the case of severely mentally disabled people, people who in some cases have been following the same stereotypes such as rocking and gyrating for decades with only brief interruptions, people who frequently injure themselves in what we see as unmotivated auto-aggressions, people who may not be able to communicate in a suitable form throughout their lives.

In my opinion, the value of a person's life is often too quickly equated with the social utility value, with one's own ideas of a valuable and fulfilling life. This includes education and vocational training, independent housekeeping as an adult with or without a family, etc.

If, in our high-tech world, someone is dependent on help throughout their life, and almost all of our students are, i.e. if someone is anything but useful to society and their reproduction, then it seems as if the fundamental value of this human being's life is prematurely called into question, simply because the value of life and the value of usefulness are inadmissibly equated. The fact that these thoughts about the problem of life being worthy or unworthy of life actually arise in many people's minds can be seen, for example, in case law. The eugenic indication for abortion according to § 218 StGB allows an expectant mother to abort her presumably damaged child up to the 22nd week (i.e. into the 6th month of pregnancy), whereas this is prohibited by law for the expectant mother of a healthy child.

As far as parents and families with a mentally disabled child are concerned, we all know about their existential problems or can more or less only guess at them. In this context, I would like to point out the many disappointments and setbacks with the disabled child, the reservations and prejudices of the environment towards the parents and the child and the self-doubt, fears and feelings of helplessness of the parents, often especially the mothers who are left alone.

A lot of educational work is still needed here, especially in the social environment, e.g. in relatives and neighborhoods, in order to reduce feelings of guilt on the part of parents on the one hand and unjustified accusations from contemporaries on the other, whether they are spoken or only thought. The following sentence applies here: "No one can blame themselves for not being affected as a parent!" Even today, the problem of the value of being human, especially for the mentally handicapped, has ultimately not been solved; even today, the Levana principle has a very current and concrete meaning, especially with regard to modern genetic engineering.

I would like to quote Prof. Dr. Meyer, Chair of Education for the Mentally Handicapped at the University of Dortmund, here: "The assessment of mentally handicapped people has not fundamentally changed over the last few centuries, nor have the consequences drawn from this. If in ancient Rome the decision regarding the value of life and thus the right to life of a disabled person was made immediately after birth, and in National Socialist Germany practically at all ages, in the present it can be made at an even earlier point in time" (MEYER 1984, 450). A very harsh statement, but one that gives pause for thought. There is no doubt that much has been achieved in recent decades for the benefit of mentally handicapped people. Initiatives by affected parents have led to the creation of more and more good facilities, and modern efforts to normalize the living conditions of mentally handicapped people, for example in workshops and homes, are certainly to be welcomed. The problem of a life unworthy of life is also less a German problem than a general human one.

There is certainly no universally valid answer here. But this seems to be certain: The more the person who is not affected imposes his view of things, his world view on the mentally disabled person, the less he encounters him through active interaction and actually gets to know him, the less he will ultimately be able to understand him. However, if he succeeds in putting his own ideals of life aside and meeting the mentally disabled person without reservation, engaging with him, the more he will be able to discover unexpected, often even unknown values in his neighbor, such as feelings of warmth, joy, affection and naturalness.

Visitors to our school often report afterwards how happily amazed they were by our pupils, how they were approached and greeted unreservedly by the disabled children and young people, how they were asked and encouraged by them to join in. Those who seek out encounters with disabled people have the opportunity to experience the undeniable value of being human. The encounter and contact between disabled and non-disabled people is therefore a prerequisite for the realization of the Levana principle, i.e. the fundamentally unconditional acceptance of fellow human beings.

"Levana" is therefore not only a name that recalls valuable initial efforts to educate and train mentally disabled people, but also a reminder of the still unresolved problems surrounding the unconditional acceptance of disabled people in the present and future. If "Levana" is only made possible through encounters and contacts, then the nameplate outside the front door of the "Levana School" can be seen as a warm welcome to every visitor.

"Levana" - a name that obliges us all!

Literature

Jean Paul, Levana oder Erziehlehre, in Jean Paul: Werke 5. vol.

Munich 1984. p. 515-874.

Meyer, H. Opinion on A, Möckel's review of the "Geschichte

der Sonderpäd... in ZfH 1984 Heft 6, p. 450 - 451.

Möckel, A. Historical and social aspects of pedagog. Förderg.

Mentally handicapped i. Geist. Behg. (Ztschrift) 1/84 p. 3 -19.

Selbmann, F., ? Jan Daniel Georgens - Life and Work - Diss. Giessen 1982.

Selbmann, F., - First approaches to a pedagogy for the mentally handicapped.

The ideas of J, D. Georgens, in: Geistige Behinderung

(Ztschrift) 4/83, p. 292 - 302.

Supplement to the LEVANA principle in 1994

(from Festschrift: 20 Jahre Schule für Geistigbehinderte 1974 bis 1994 Levana-Schule Bad Neuenahr-Ahrweiler, p. 38 - 41)

Gerd Jung

Since our school was given its name more than 7 years ago, developments have taken place in the scientific debate in the specialist discipline of education for the mentally handicapped and its environment, particularly in the Federal Republic of Germany, which have not remained without influence on the LEVANA idea.

From the large number of publications in specialist literature and the daily press, we would like to mention two areas that are closely linked to the name of our school.

A changed view of the human being in disability education

In the past, particularly when special needs education, especially education for the mentally handicapped, was established, the special nature of people with intellectual disabilities was emphasized in a distancing view of humanity. The focus was and still is sometimes on the idea of differentiation, e.g. in what area and to what extent disabled people deviate from the statistical norm established by non-disabled people. This was associated with the idea of exclusion and isolation.

More recent developments see people with disabilities in the world we all live in from an ecological perspective. This integrated view of human beings emphasizes people and their similarities with other people. The >mentally disabledperson with a mental disability<, i.e. the disability is merely a characteristic. While the disabled person, or rather the person with a disability, from the point of view of an integrated view of humanity is therefore included in humanity and remains integrated in society, from the point of view of a distancing view of humanity he is on the fringes or outside of society ? in extreme cases, as recent history shows, he is even outside of humanity (euthanasia).

Educational descriptions focus less on deficits and more on a child's individual support needs.

In addition, positive characteristics of people with intellectual disabilities are increasingly emphasized as so-called qualities of the heart, such as sincerity, trust, enjoyment of the simple things in life, and the positive influence they can have on family members and friends? a step forward from the exclusively negative view of the past. Another positive trend is the recognition of people with disabilities as partners in dialog. In self-help groups, for example, people with intellectual disabilities themselves have their say, and in some places they have a seat and a voice on boards of directors or employee representatives. Even in the case of people with severe intellectual disabilities, support and teaching no longer takes the form of functionalist treatment (e.g. basal stimulation), but instead attempts to build up an I-Thou relationship based on partnership. Disruptive behavior should not simply be developed through behavioral therapy measures, but should first be understood in terms of the individual's subjective search for meaning.

Other current developments, such as from specialization to holism, from segregation to integration, are only mentioned here.

A changed image of humanity in society

The trends in educational theory and practice outlined above could lead to a certain optimism. However, this is hardly appropriate at present. Pedagogy does not take place in a social vacuum. The current trends in society shown here run counter to the positive developments in pedagogy.

- Exclusion from educational opportunities: The right to education is in danger

In some federal states, attempts are again being made to circumvent compulsory schooling for children with severe intellectual disabilities by using descriptions such as >not able to live in the communityrequiring too much care and support<. It still applies to our school that every mentally disabled person must be included in educational support measures regardless of the type and severity of their disability.

- The new hostility towards the disabled: social integration is in danger

Despite strong efforts, particularly in the field of education, to increase tolerance and integration efforts towards marginalized groups in society, a current tendency to segregate people who are different, whether they are foreigners or disabled, cannot be overlooked. One example among many is the scandalous Flensburg ruling that awarded a married couple a reduction of DM 350 for eating together with a group of severely disabled people in a hotel because of the >disgusting sight<. Complaints and objections from neighbors prior to the construction of apartments for the disabled in residential areas are not uncommon.

The looming childcare shortage makes it clear that, despite high unemployment, fewer young people are opting for social professions than in the past.

- Violence against disabled people: physical integrity is at risk

Increasingly, defenceless people with disabilities are also victims of violent racist criminals.

Above all, murder and bomb threats against schools for disabled children and harassment, verbal abuse, assaults and abuse in public are frightening.

- Discussions on the lack of value of life: Life is in danger

Due to advances and the expansion of prenatal diagnostics, social pressure on pregnant women to find out about the health of their unborn child through an amniocentesis is increasing. If irregularities are detected, termination of pregnancy is the rule and is also permitted in the new Section 218 through a special period of 22 weeks for embryopathic indications, instead of the 12 weeks that would otherwise apply.

Irrespective of the decision of conscience, which can only be made by the pregnant woman herself, the pressure on her to make use of all technical possibilities to prevent the birth of a disabled child in line with social expectations is intensified. The birth of a disabled child thus threatens to be judged exclusively as an individual omission, with consequences in terms of responsibility and solidarity.

It is also often overlooked that disabilities can develop during or after birth in infancy or early childhood.

It is alarming that there is an increasing public debate about the value of the lives of people with disabilities who have already been born.

For example, an Australian philosopher calls for parents to be granted the right to kill their disabled child in a rational ethics book, which was published in a well-known German paperback series. The killing of an infant with Down's syndrome (formerly Mongolism) is not the same as the killing of normal human beings, as a developing personality cannot be assumed here.

Killing is specifically described as the deprivation of food or vital medication.

Dear reader,

Stay vigilant with the parents and friends of our students, take advantage of the opportunities to meet people with intellectual disabilities, only then will you have the chance to experience the undeniable value of this fellow human being!

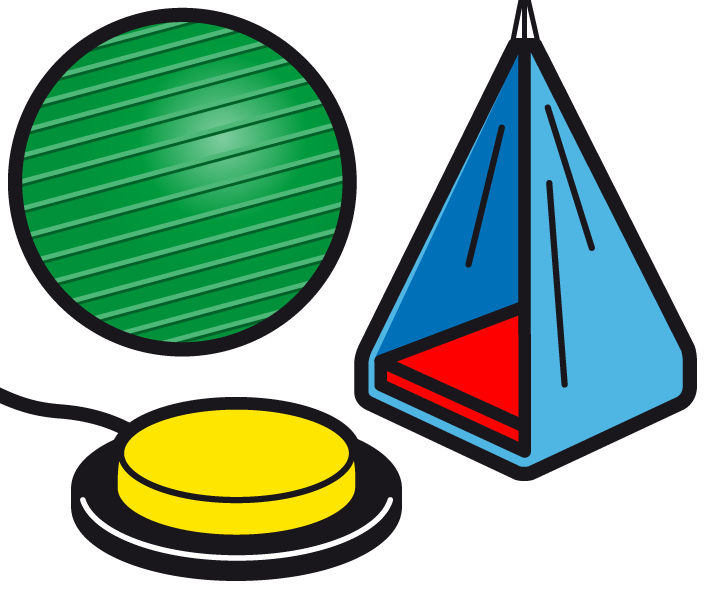

The emblem of our school refers to the Roman Levana rite. It represents the hand of an adult holding a newborn child, whether disabled or not, firmly and securely. Our emblem thus calls on us all to ensure that every person, regardless of their individual characteristics and features, is guaranteed their fundamental right to life and human acceptance and their right to education and participation in public life.

The LEVANA principle

remains a current obligation!

Statement of principle 1993:

We have something to say!

You must listen to us when we communicate.

(Committee Self Advocacy Utrecht 1993)